Tržiště 15, Lower Side

In March 1917 Kafka rented a two-room flat in the Schönborn Palace for himself and also for his bride Felice. The palace had been rebuilt around the middle of the 17th century by the then owner, the Maltese Grand Master Rudolf Colloredo-Waldsee, in the early baroque manner; in 1794 it became the property of the Schönborn Counts. Today it is the siege of the USA ambassadorial headquarters.

In March 1917 Kafka rented a two-room flat in the Schönborn Palace for himself and also for his bride Felice. The palace had been rebuilt around the middle of the 17th century by the then owner, the Maltese Grand Master Rudolf Colloredo-Waldsee, in the early baroque manner; in 1794 it became the property of the Schönborn Counts. Today it is the siege of the USA ambassadorial headquarters.

At the time of Kafka, the Vegetable Market extended out in front of it, a street market with a most varied collection of vegetable-stands.

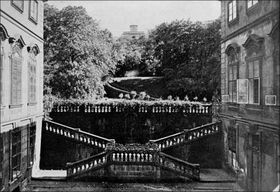

He wrote to Felice Bauer: “About that time I came back from Munich with new courage, went to a rental agency, where almost as the first choice an apartment in one of the most beautiful city palaces was offered to me. Two rooms, an antechamber, whose one half was furnished as a bathroom. Six hundred crowns a year. It was the fulfillment of a dream. I went there. The rooms with high ceilings and beautiful, red and gold, a little like in Versailles. Four windows looking out onto a dreamy quiet courtyard, one window onto the garden. The garden! Entering through the gate of the castle, you can hardly believe your eyes. Through a second gate flanked by caryatides you can see ascending to a Gloriette (columned portico) slowly and expansively an extensive slope with a nicely laid-out flight, of stone steps winding back and forth and interrupted by branch-paths leading off it. Now, the apartment did have one little flaw. The tenant to date, a young man, who lived separated from his wife, had conducted his households here for a few months along with his manservant, was then unexpectedly transferred (he’s an official), had to leave Prague, but had already invested so much in the apartment in such a short time, that he didn’t want to give it up that easily. So therefore he kept it and looked for someone who would, at least partially, cover his expenses (introduction of electric light, furnishing the bathroom, constructing built-in closets, installing a telephone, a large spread-out carpet). I wasn’t that someone. He wanted six hundred fifty crowns for all this (certainly little enough).

He wrote to Felice Bauer: “About that time I came back from Munich with new courage, went to a rental agency, where almost as the first choice an apartment in one of the most beautiful city palaces was offered to me. Two rooms, an antechamber, whose one half was furnished as a bathroom. Six hundred crowns a year. It was the fulfillment of a dream. I went there. The rooms with high ceilings and beautiful, red and gold, a little like in Versailles. Four windows looking out onto a dreamy quiet courtyard, one window onto the garden. The garden! Entering through the gate of the castle, you can hardly believe your eyes. Through a second gate flanked by caryatides you can see ascending to a Gloriette (columned portico) slowly and expansively an extensive slope with a nicely laid-out flight, of stone steps winding back and forth and interrupted by branch-paths leading off it. Now, the apartment did have one little flaw. The tenant to date, a young man, who lived separated from his wife, had conducted his households here for a few months along with his manservant, was then unexpectedly transferred (he’s an official), had to leave Prague, but had already invested so much in the apartment in such a short time, that he didn’t want to give it up that easily. So therefore he kept it and looked for someone who would, at least partially, cover his expenses (introduction of electric light, furnishing the bathroom, constructing built-in closets, installing a telephone, a large spread-out carpet). I wasn’t that someone. He wanted six hundred fifty crowns for all this (certainly little enough).  Schönborn PalaceIt was too much for me and also the exaggeratedly high, cold rooms were too splendid, and to top it all off, I also didn’t have any furniture, small considerations were added to that. But there just happened to be another apartment in the same palace, on the second (third) floor, rented out by the building-administration itself, somewhat lower rooms, view out onto the street, the Hradčany moved very close to the window. Friendlier, more human, modestly furnished; a countess, who was a guest here, probably with more modest demands, had lived here, the girlish furnishings consisting of old furniture was still standing there.”

Schönborn PalaceIt was too much for me and also the exaggeratedly high, cold rooms were too splendid, and to top it all off, I also didn’t have any furniture, small considerations were added to that. But there just happened to be another apartment in the same palace, on the second (third) floor, rented out by the building-administration itself, somewhat lower rooms, view out onto the street, the Hradčany moved very close to the window. Friendlier, more human, modestly furnished; a countess, who was a guest here, probably with more modest demands, had lived here, the girlish furnishings consisting of old furniture was still standing there.”

Kafka had just half-way become settled down in the Schönborn Palace, when in the night of August 12 to 13, he suffered a lung hemorrhage. Already earlier that month he had coughed up some blood while swimming in the Civilian Swimming School, but refused to recognize anything disturbing in that. Now there were no doubts anymore in the gravity of his illness – tuberculosis. Kafka later wrote to Milena Jesenská: “About 3 years ago it began in the middle of the night with a hemorrhage. I got up, perturbed as one is by everything new (instead of remaining lying down, as I later learned one should do), naturally somewhat startled, walked around in the room, went to the window, leaned out, went to the washstand, walked around in the room, sat down on the bed – continually blood. At the same time I was not unhappy, because it downed on me for a specific reason that after 3, 4 sleepless years – assuming that the bleeding stopped – I would be able to sleep for the first time. And it stopped (hasn’t appeared again since then) and I slept the rest of the night. In the morning, however, the girl who did cleaning came (at that time I had an apartment in the Schönborn Palace), a good, very devoted, but extremely matter-of-fact girl, saw the blood and said: ‘Pane doktore, s Vámi to dlouho nepotrvá.’ – ‘Doctor, it doesn’t last long with you.’ But I felt better than usual, I went to the office and to the doctor only in the afternoon. The further story is immaterial here.”

The window of Kafka's flat in Schönborn Palace

Kafka also confided to his sister Ottla about the event; he kept it secret from his parents.

“One night perhaps three weeks ago I had a horrible coughing fit where my lings bled. Around four in the morning I wake up surprised at the amount of saliva in my mouth, I spit it out, I turn on the light anyway, and the strange thing is I see clots of blood. And then it started. I don’t know if I’m spelling it right but in Czech they call it “chrlení” (gargling), which is an accurate expression for this oozing from the throat. I thought that it might never stop. How can I plug this spring when I didn’t release it. I got up and paced the room several times, approached the window, looked outside, went back – the blood kept coming, and finally it stopped and I felt asleep, sleeping longer than I had in so long.”

The window of Kafka's flat in Schönborn Palace

Kafka also confided to his sister Ottla about the event; he kept it secret from his parents.

“One night perhaps three weeks ago I had a horrible coughing fit where my lings bled. Around four in the morning I wake up surprised at the amount of saliva in my mouth, I spit it out, I turn on the light anyway, and the strange thing is I see clots of blood. And then it started. I don’t know if I’m spelling it right but in Czech they call it “chrlení” (gargling), which is an accurate expression for this oozing from the throat. I thought that it might never stop. How can I plug this spring when I didn’t release it. I got up and paced the room several times, approached the window, looked outside, went back – the blood kept coming, and finally it stopped and I felt asleep, sleeping longer than I had in so long.”

The family doctor whom he soon contacted diagnosed a bronchial infection. On the advice of Max Brod Kafka had himself examined by a lung specialist in addition, although he had already come up with his own interpretation of the illness: “It was this way: the brain couldn’t bear the cares and pain that had been inflicted on it. It said: ‘I give up; if there is anyone here who is still interested in maintaining the whole body, then he should relieve me of some of my burden and it can continue a little while longer.’ That’s when the lung reported for duty.”

Tuberculosis was also an opportunity for early retirement. In a jiffy Kafka applied for retirement on September 6, 1917, at first, of course, without success. But nevertheless he was granted a three month vacation to recuperate and he wanted to spend it in a rural idyll with his sister in Siřem. At this time Kafka had to give up his domicile in the Schönborn Palace: “Dear Ottla, well, I've moved out. I closed the windows in the palace for the last time, locked the door, how similar that must be to dying.”